The Real Dick Whittington

History of the Lord Mayor’s Show The Real Dick Whittington

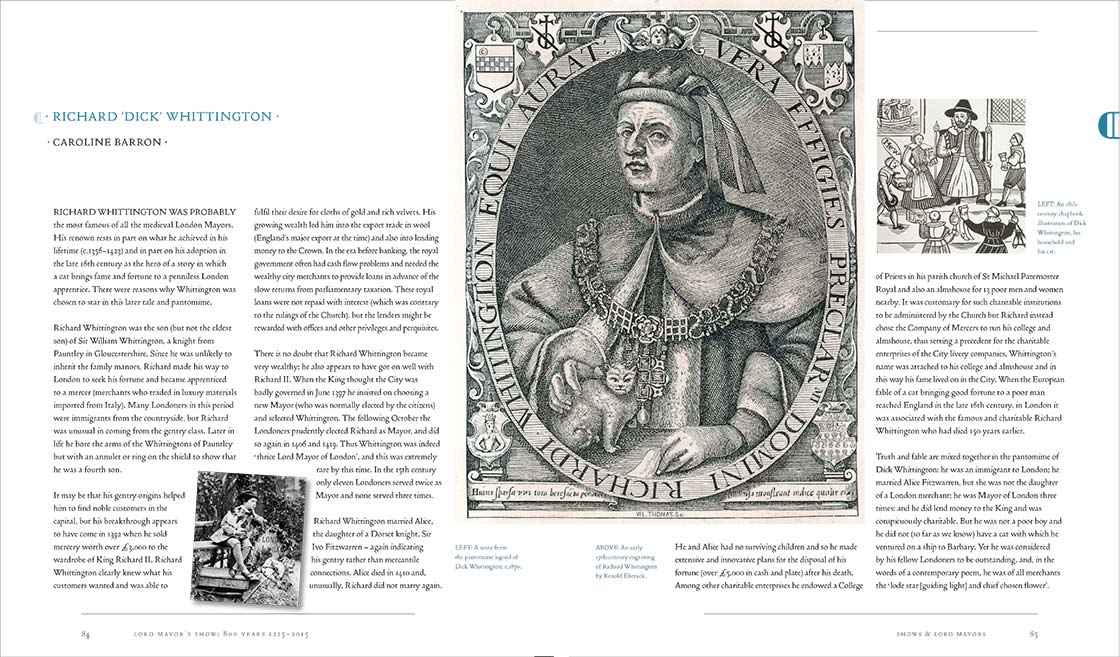

Richard Whittington was probably the most famous of all the medieval London Mayors. His renown rests in part on what he achieved in his lifetime (c.1356–1423) and in part on his adoption in the late 16th century as the hero of a story in which a cat brings fame and fortune to a penniless London apprentice. There were reasons why Whittington was chosen to star in this later tale and pantomime.

Richard Whittington was the son (but not the eldest son) of Sir William Whittington, a knight from Pauntley in Gloucestershire. Since he was unlikely to inherit the family manors, Richard made his way to London to seek his fortune and became apprenticed to a mercer (merchants who traded in luxury materials imported from Italy). Many Londoners in this period were immigrants from the countryside, but Richard was unusual in coming from the gentry class. Later in life he bore the arms of the Whittingtons of Pauntley but with an annulet or ring on the shield to show that he was a fourth son.

It may be that his gentry origins helped him to find noble customers in the capital, but his breakthrough appears to have come in 1392 when he sold mercery worth over £3,000 to the wardrobe of King Richard II. Richard Whittington clearly knew what his customers wanted and was able to fulfil their desire for cloths of gold and rich velvets. His growing wealth led him into the export trade in wool (England’s major export at the time) and also into lending money to the Crown. In the era before banking, the royal government often had cash flow problems and needed the wealthy city merchants to provide loans in advance of the slow returns from parliamentary taxation. These royal loans were not repaid with interest (which was contrary to the rulings of the Church), but the lenders might be rewarded with offices and other privileges and perquisites.

There is no doubt that Richard Whittington became very wealthy; he also appears to have got on well with Richard II. When the King thought the City was badly governed in June 1397 he insisted on choosing a new Mayor (who was normally elected by the citizens) and selected Whittington. The following October the Londoners prudently elected Richard as Mayor, and did so again in 1406 and 1419. Thus Whittington was indeed ‘thrice Lord Mayor of London’, and this was extremely rare by this time. In the 15th century only eleven Londoners served twice as Mayor and none served three times.

Above: a spread from Lord Mayor’s Show: 800 Years 1215-2015. Main image: Whittington at Highgate by Gustav Doré

Richard Whittington married Alice, the daughter of a Dorset knight, Sir Ivo Fitzwarren – again indicating his gentry rather than mercantile connections. Alice died in 1410 and, unusually, Richard did not marry again.

He and Alice had no surviving children and so he made extensive and innovative plans for the disposal of his fortune (over £5,000 in cash and plate) after his death. Among other charitable enterprises he endowed a College of Priests in his parish church of St Michael Paternoster Royal and also an almshouse for 13 poor men and women nearby. It was customary for such charitable institutions to be administered by the Church but Richard instead chose the Company of Mercers to run his college and almshouse, thus setting a precedent for the charitable enterprises of the City livery companies. Whittington’s name was attached to his college and almshouse and in this way his fame lived on in the City. When the European fable of a cat bringing good fortune to a poor man reached England in the late 16th century, in London it was associated with the famous and charitable Richard Whittington who had died 150 years earlier.

Truth and fable are mixed together in the pantomime of Dick Whittington: he was an immigrant to London; he married Alice Fitzwarren, but she was not the daughter of a London merchant; he was Mayor of London three times; and he did lend money to the King and was conspicuously charitable. But he was not a poor boy and he did not (so far as we know) have a cat with which he ventured on a ship to Barbary. Yet he was considered by his fellow Londoners to be outstanding, and, in the words of a contemporary poem, he was of all merchants the ‘lode star [guiding light] and chief chosen flower’.